What If It’s Too Tall?

And Martha Stewart’s favorite natives

Dear Heather, Do you have any tips for visualizing the size of trees and shrubs? I really struggle with height especially, so I’ve been hesitant about planting them. — Jess

Use your body. And your house. I’ll explain how in a moment, but I encourage you to dive in and plant. Now. The risk of underestimating eventual height is small compared to the frustration of waiting for shrubs and trees to grow — a frustration I feel acutely. Privacy hedges can be especially unattractive as they grow in, with big gaps between scrawny shrubs.

When big is a problem

Foundations are the one place where homeowners underestimate mature size. They plant shrubs that eventually cover windows and trees that crowd awkwardly against the siding. I tend to prefer to push shrubs and trees away from the house into the yard to create rooms, act as focal points, provide privacy, screen views, or soften a fence.

If you want foundation plantings, stick to shrubs and choose the size and location carefully. But don’t get too hung up on this. If you later determine a shrub or tree is too tall, you can prune them or move them. In fact, you can cut most shrubs down to less than a foot, called coppicing, and they will grow back thick and healthy over several years.

Visualizing size

I encourage you to think about sizes relative to yourself and your house. That’s what matters in terms of how they will feel in your yard. Here are some common shrub and tree heights as examples:

Small shrub (3-4’): Hip to chest high

Medium to tall shrub (6-10’): Your height to tips of fingers raised overhead

Small tree (15’): Tall as your second floor windows

Medium tree (25’): Tall as a two-story house

Tall tree (50’): Really, f-ing tall — but probably not in my lifetime

My favorite way to visualize size is to ask Pete or Zoe to act like a shrub or tree, then view them from every possible angle, including from inside the house. Standing with arms outstretched, they are roughly the height and diameter of a medium-sized shrub. With arms overhead, and a lot of imagination, they are the trunk of a tree. Sure, they look ridiculous, but that’s part of the fun.

If you have an iPad, you can get a sense of proportion by sketching a tree on a photograph of your house or another background against which you’ll see the tree. Use elements within the photo (e.g., the house height) to size your tree, keeping in mind that objects appear larger when they are closer. Landscape designer Liza Kiesler describes how she uses such “doodles” as follows:

[I]n the first phases I tend to make overlay sketches to test out shape, mass and proportion. In the back of my mind I am always keeping in mind what excites me most- the experience and atmosphere I want to create for the owners- how the garden will feel to walk through, where the light will hit. — Viburnum Gardens Instagram

Estimating tree sizes over time

Zoe and I created a model to help our students choose the right size and types of trees for their designs, based on their budgets and patience. Take this with a big grain of salt, because plant information is inconsistent and plant growth rates vary on a whole variety of factors. But we think it’s better than nothing.

Plants grow at different rates depending on conditions. Trees are grouped into growth rates:

<1’ = slow

1-2’ = moderate

>2’ = fast

In the first couple of years after you install them, these rates are affected by transplant shock. As you may have heard, transplanted trees and shrubs sleep the first season, creep the second season, and leap the third season. That means they start to grow at their normal rate in the third season; they may grow about half as much the second season. So they only grow about 1 ½ years’ worth in their first three seasons.

The real risk: Too small

Did you notice from the above chart that NONE of these tree sizes grow to more than 32 feet in 10 years? The average homeowner tenure is about 12 years (almost double what it was 20 years ago) so it’s likely that oak won’t reach 100 feet while you’re around to see it.

If you want to enjoy a substantial tree — say 14 feet or more — within three years, you’ll want to plant at least a 7-foot fast-growing tree or a 9-foot moderate-growing tree. Those would be in 10 or 15 gallon pots.

Now, there are faster growing trees — some grow up to four feet a year, twice as fast as the fast-growing example — but even those don’t really kick in until year three, so please keep that in mind.

In the meantime, both you and wildlife are losing out as you hesitate. So as you allocate your budget and phase your plantings over the next few years, I’d like you to keep in mind this Chinese proverb…

“The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is now.” — Chinese Proverb

— Heather

P.S. If you haven’t signed up for Less Lawn, More Life yet, I hope you will. It’s right in line with everything we care about at Design Your Wild — making our yards better for biodiversity, bit by bit. You can read more about it in Zoe’s update here.

10 Weekends to Wild Challenge #6: Note what’s blooming

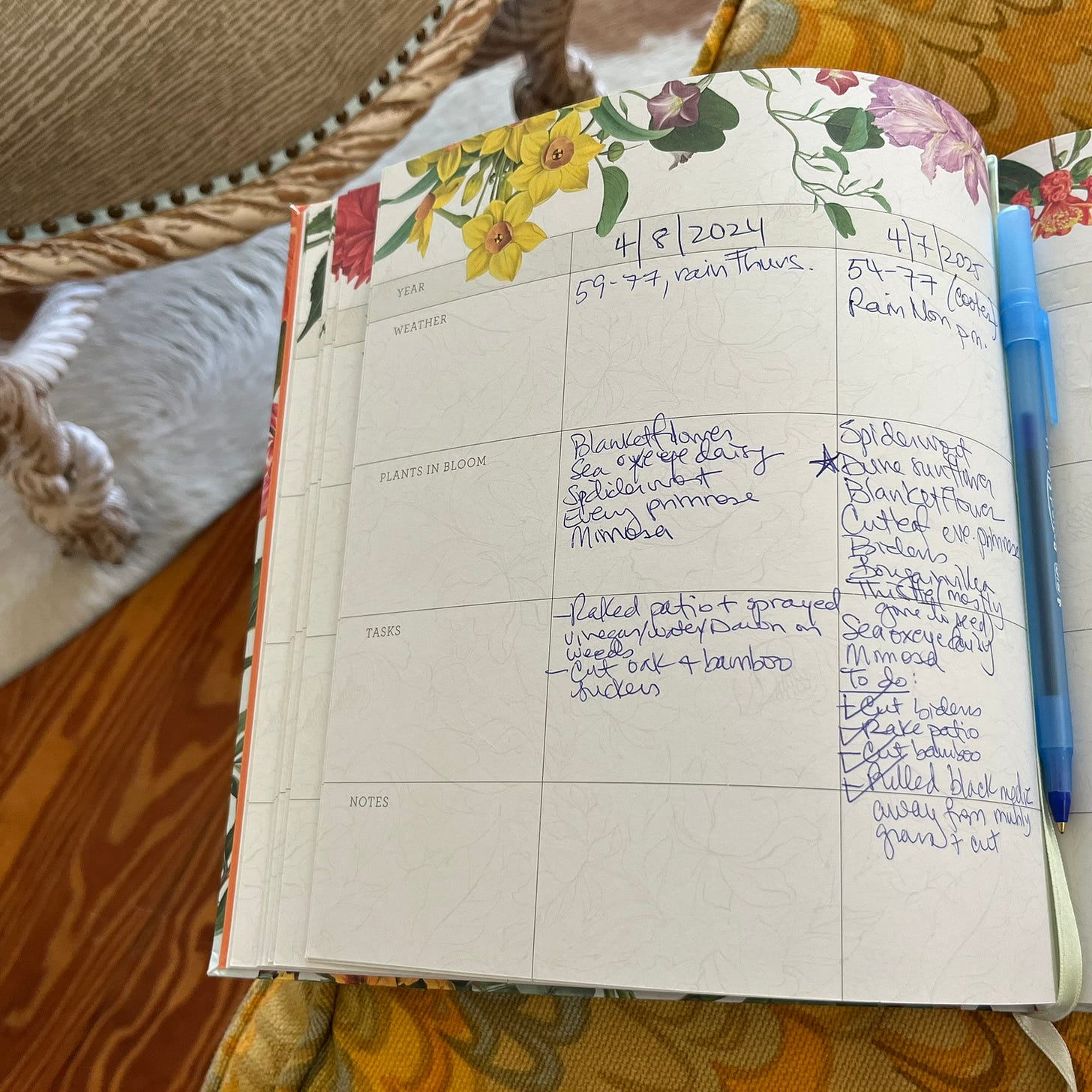

I hope you’re making a habit of a daily stroll around your yard (Challenge #6). Now, once a week, jot down what’s blooming and note the current star of your garden. I do this each Monday in the RHS Gardener's Five Year Record Book, where I also note the weather outlook and, as I complete them, gardening tasks. While it’s valuable as a record of how my garden is developing over time, I think the main value is reflecting on how the garden is changing week to week, as new species emerge and others fade.

ICYMI

Challenge #1: Check your winter views

Challenge #2: Score some seating

Challenge #3: Name your theme

Challenge #4: Get thee to a nursery!

Challenge #5: A daily stroll

Why, How, Wow!

Why?

Have you been seeing the headlines claiming native plants aren’t so important? For example, “Here’s Why You Don’t Need to Focus Too Much on Planting Natives, According to Martha Stewart” from Veranda.

I was so disappointed when this popped up in my feed! Martha Stewart was an early supporter of planting natives. Has she abandoned the good fight? Fortunately not. An excerpt from her new book in Good Housekeeping sets the record straight:

Native plants are the heart of a healthy ecosystem, removing carbon from the air, providing shelter and food for wildlife, and promoting biodiversity. … A plant that is native to an area grows there naturally, without any cultivation. It is also cold-hardy for the area, though that same plant is not necessarily cold-hardy in other areas within the same zone or region where it is not native. Picture the vastly different natural landscapes in Utah and Kentucky (both in zones 5–7) or Montana and Maine (zones 2–5) — or even a rural, inland county versus coastal towns in South Carolina (zones 8–9). Numerous studies have shown that native plants support more species and larger numbers of bees than non-native plants, too. — Martha Stewart's Gardening Handbook

Thank you, Martha and Good Housekeeping. And shame on you, Veranda, for publishing misleading contrarian drivel as click bait. (I’m sorry to say, it worked.)

How

Martha’s excerpt concludes with a sampling of plants native to Pennsylvania, many of which are broadly native east of the Rockies. Doesn’t this delicate, pink-forward selection just scream Blooming Romantic Yardenality™? If you’re also a Blooming Romantic at heart, here’s a how-to with recommended natives from each major eco region: English Flower Garden Ideas.

Here’s the key to Martha’s palette above:

1. Rattlesnake master (Eryngium yuccifolium)

2. Goldenrod (Solidago speciosa)

3. ‘Little Henry’ sweet coneflower (Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’)

4. Butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa)

5. Hubricht’s bluestar (Amsonia hubrictii)

6. Tennessee purple coneflower (Echinacea tennesseensis)

7. ‘Autumn Bride’ coral bells (Heuchera villosa ‘Autumn Bride’)

8. Muhly grass (Muhlenbergia capillaris)

9. Aster spp.

10. White snakeroot (Ageratina altissima)

11. Blue wood aster (Aster cordifolius, syn. Symphyotrichum cordifolium)

12. ‘Proud Berry’ coralberry (Symphoricarpos orbiculatus ‘Proud Berry’)

13. Joe-pye weed (Eupatorium dubium)

Wow!

Here’s another example of a garden in transformation by Liza Kiesler, showing how the trees looked in her sketch and then in the ground. Note that the tree on the left is a northern red oak, a fast-growing tree that can reach 120 feet tall. The tree on the right is American hornbeam, a medium-sized tree that may eventually reach the roofline of this house. Liza’s sketch shows how the selected trees look soon after installation (though the oak won’t hold a swing for quite a few years).

Note the lack of traditional foundation shrubs. Instead, there is a mixture of forbs — sedges, ferns, and wildflowers.

These folks are enjoying seeing hummingbirds coming to the echinacea right outside the kitchen window! — Viburnum Gardens on Instagram

You might laugh...in my daily stroll, I'm often waylaid by one of the "stops" I planned in the gazebo. I'd never utilized it before taking your class this winter. Now it has a wind chimes, several cozy chairs, an art table, I just made curtains from string and leftover jewels that my girls must have had from Girl Scouts years ago. My reward has been watching a mama robin who finds worms, sits at almost the exact same spot on the utility wire until it is safe, and then swoops down into her nest. I'm upcycling some dreadful plastic pots with acrylic paint and intend on planting zinnias in them after Mother's Day to go on each step up into the gazebo. It's been fun.