And Now: A Lot of Whys

Warning! Downer data ahead

Dear Yardener,

When I saw my “upcoming topics” document had reached 26 single-spaced pages, I imagined this column as a breezy zip through months of collected links and images. Sadly, reorganizing the collected miscellany into my “Why, How, Wow!” format revealed some grim “Why?” stats unanswerable with ecological landscaping “Hows.” But the information is important, so I hope you’ll stick with me — and even click some of the links to learn more — until you reach the gorgeous before-and-after images in “Wow!”

— Heather

P.S. Please use the buttons at the bottom to like and comment. Your feedback fuels my work! And ask your ecological garden design questions to give me something cheerier to write about:)

Why, How, Wow!

Why? Studies demonstrate benefit of nature to humans while nature connectedness — and nature itself — declines

In wildness is the preservation of the world. — Henry David Thoreau, 1851

A Washington Post article on forest bathing presents some of the evidence-based benefits of being in nature:

[Dr. Susan Abookire, an internist and professor at Harvard Medical School] explained that just by standing among the trees, we were inhaling essential tree oils called phytoncides and aromatic plant compounds called terpenes. “There’s several studies now showing that inhaling phytoncides boosts our immune system, and specifically our natural killer-cell numbers and activities go up,” she said. “And there are a lot of studies going on — NIH, others, many in vitro and some in vivo — showing how terpenes are cytotoxic and anti-tumorigenic, they’re neuroprotective, etcetera.”

In a 90-minute webinar for health care professionals called “Nature as Medicine,” Abookire cites study after study showing the benefits: lower blood pressure and anxiety; reduced stress-hormone levels; improved memory, attention, mood and sleep; faster recovery from surgery and illness; healthier gut microbiomes and more. — Washington Post

Unfortunately, fewer and fewer people are receiving these benefits. A recent English study found people’s connection to nature has declined by more than 60 percent since 1800.

Computer modelling predicts that levels of nature connectedness will continue to decline unless there are far-reaching policy and societal changes — with introducing children to nature at a young age and radically greening urban environments the most effective interventions.

The study by Miles Richardson, a professor of nature connectedness at the University of Derby, accurately tracks the loss of nature from people’s lives over 220 years by using data on urbanisation, the loss of wildlife in neighbourhoods and, crucially, parents no longer passing on engagement with nature to their children. — The Guardian

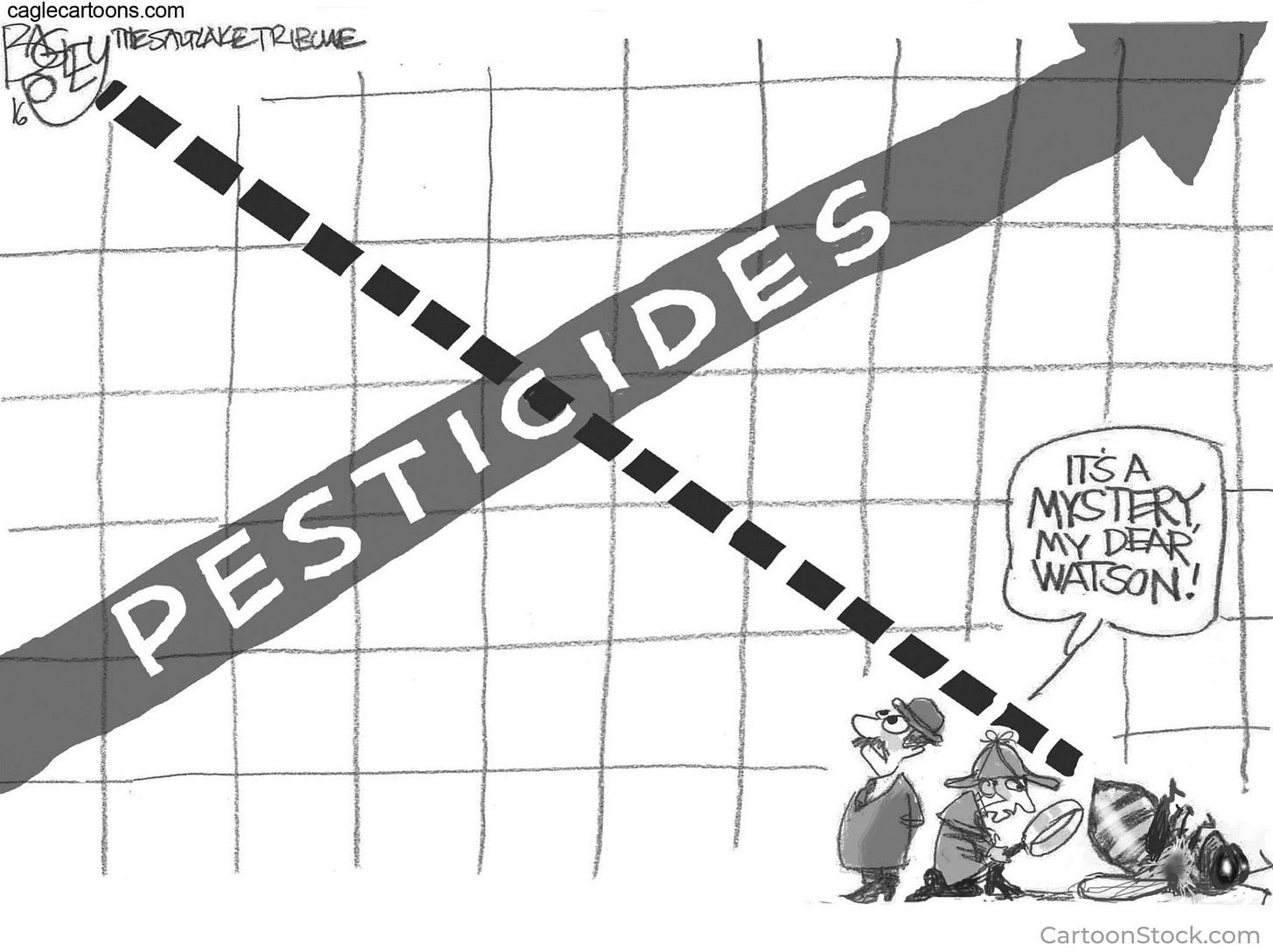

Meanwhile, widespread agricultural and landscape maintenance practices continue to harm both people and wildlife. Studies of people living near golf courses, for example, demonstrated a relationship between those landscapes and Parkinson’s disease.

Dorsey and his colleagues found in a study this year that people living within a mile of a golf course were more than twice as likely to be diagnosed with Parkinson’s compared with those living six or more miles away. And residents of a public water district with one or more golf courses had almost double the odds of developing Parkinson’s compared with those without a course. Another study, from 2009, showed that consuming water from private wells located in areas with documented historical pesticide use resulted in an approximately 70 to 90 percent increase in the relative risk of Parkinson’s. — The Washington Post

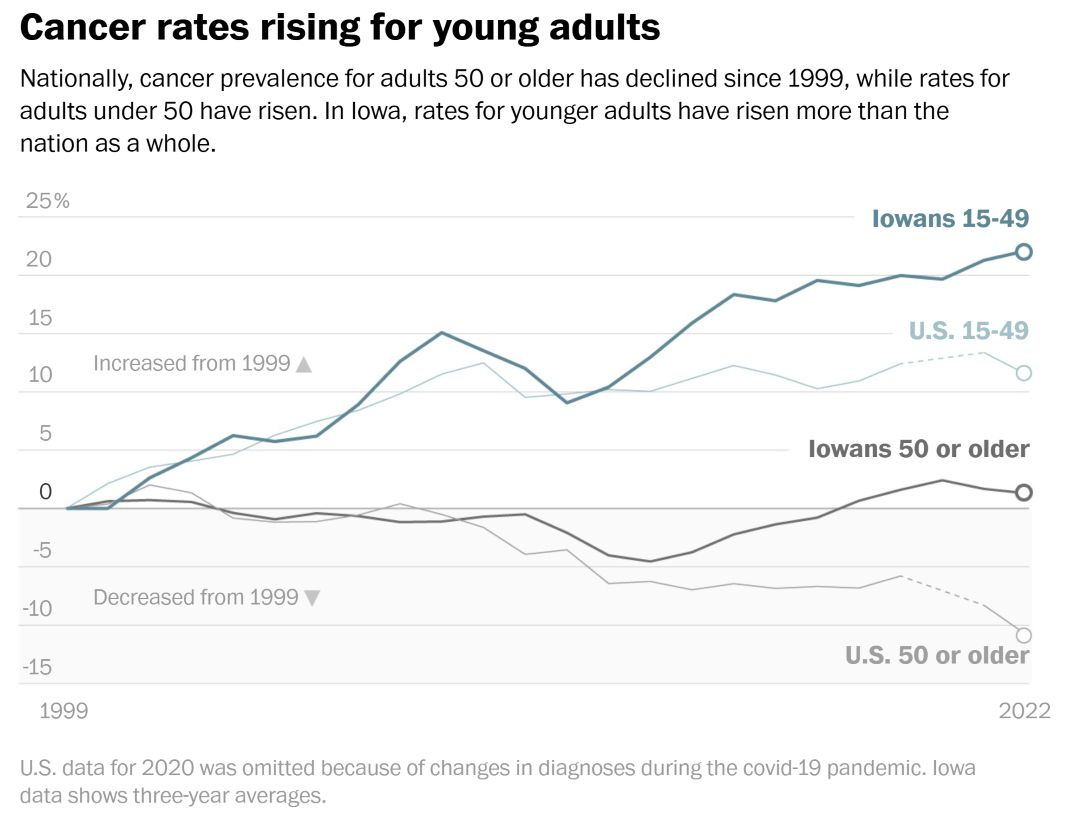

And deeply frightening is the rise in cancer rates — especially blood-related cancers like leukemia — among young people in Iowa and other midwestern agricultural states, as reported this month by The Washington Post.

Glyphosate is a likely cause. Despite having been removed from consumer formulations, glyphosate is still the most-used herbicide worldwide, broadly used by farmers and landscape professionals. (To find the level of glyphosate use near you, use this interactive map of glyphosate use by county.)

Weedkillers containing [glyphosate] are used on nearly half of all planted acres of corn and soybeans in the U.S., though much of those are not grown for human consumption. They’re also used on acres of farmland where wheat, oats, fruits and cotton are grown. Pesticide residue testing from the FDA found glyphosate residues on a wide variety of crops, including oats, soybeans, cranberries, grapes, raisins, oranges, apples, cherries and beans. — NBC News

While the cancer rates don’t prove causality, research published this June in Environmental Health proved a relationship between “acceptable” doses of glyphosate and cancer (notably leukemia) in rats.

A two year carcinogenicity study in rats reports increased benign and malignant tumor rates after continuous exposure to glyphosate or glyphosate-based herbicides … The exposure levels studied in this research are considered low or acceptable — Earth.com

Scientists continue to document alarming declines in butterflies, the most commonly counted insect and a bellwether for other species. For example, a paper published in March 2025 in Science, documented a 22% national butterfly decline across the United States from 2000 to 2020. The same scientists documented an even greater decline in the Midwest — no surprise given the use of pesticides, as well as herbicides, in agricultural states.

In the new study, researchers combined more than 4.3 million observations of 136 butterfly species over the past 32 years to characterize changes in butterfly biodiversity across the midwestern United States.

The authors report that 59 of the 136 species declined in abundance over the study period. And for every 10 species and 100 individuals present in a county in 1992, there are now only nine species and 60 individuals. — USA Today

In some regions of the U.S., as much as 90 percent of the monarch butterfly population has been wiped out in recent decades, and evidence has pointed to pesticides, climate crisis and habitat loss as the drivers. But it has been difficult for scientists to show a direct cause and effect link between pesticides and monarch die-off, which is why another recent study is so important.

A 2024 mass monarch butterfly die-off in California was probably caused by pesticide exposure, new peer-reviewed research finds, adding difficult-to-obtain evidence to the theory that pesticides are partly behind dramatic declines in monarchs’ numbers in recent decades.

Researchers discovered hundreds of butterflies that had died or were dying in January 2024 near an overwintering site, where insects spend winter months. The butterflies were found twitching or dead in piles, which are common signs of neurotoxic pesticide poisoning, researchers wrote.

Testing of 10 of the insects revealed an average of seven pesticides in each, and at levels that researchers suspect were lethal. Proving that pesticides kill butterflies in the wild is a challenge because it is difficult to find and test them soon after they die. Though the sample size is limited, the authors wrote, the findings provide “meaningful insight” into the die-off and broader population decline. — The Guardian

Insects decline isn’t limited to areas with high pesticide use, however. Researchers found an alarming rate of insect decline even in untouched wilderness, which they attributed to warming summer temperatures.

Keith Sockman, associate professor of biology at UNC-Chapel Hill, quantified the abundance of flying insects during 15 seasons between 2004 and 2024 on a subalpine meadow in Colorado, a site with 38 years of weather data and minimal direct human impact. He discovered an average annual decline of 6.6% in insect abundance, amounting to a 72.4% drop over the 20-year period. The study also found that this steep decline is associated with rising summer temperatures. — Phys.org

Compounding pesticide use and climate change, Americans continue to plant invasives that crowd out native vegetation, reducing insect habitat — usually out of ignorance and misplaced trust in retail nurseries.

In 2021, Dr. Beaury [assistant curator at the New York Botanical Garden’s Center for Conservation and Restoration Ecology] published research estimating that 61 percent of the 1,285 plant species identified as invasive in the United States were still available through the nursery trade. That group included 20 that were illegal to grow or sell nationally, and “species that were introduced and recognized as invasive decades ago,” she said in a recent conversation. — The New York Times

You might expect the decrease in biodiversity to reverse as human populations start to decline, as projected in 85 countries by 2050, mostly in Europe. This has not been the case in Japan, which in 2010 became the first country to begin depopulating, according to a recent large-scale study published in Nature Sustainability.

[In rural areas,] humans are agents of ecosystem sustainability. Traditional farming and seasonal livelihood practices, such as flooding, planting and harvesting of rice fields, orchard and coppice management, and property upkeep, are important for maintaining biodiversity. So depopulation can be destructive to nature. Some species thrive, but these are often non-native ones that present other challenges, such as the drying and choking of formerly wet rice paddy fields by invasive grasses.

[Despite depopulation,] in 2024, more than 790,000 [housing units] were built, due partly to Japan’s changing population distribution and household composition. Alongside these come roads, shopping malls, sports facilities, car parks and Japan’s ubiquitous convenience stores. All in all, wildlife has less space and fewer niches to inhabit, despite there being fewer people. — The Conversation

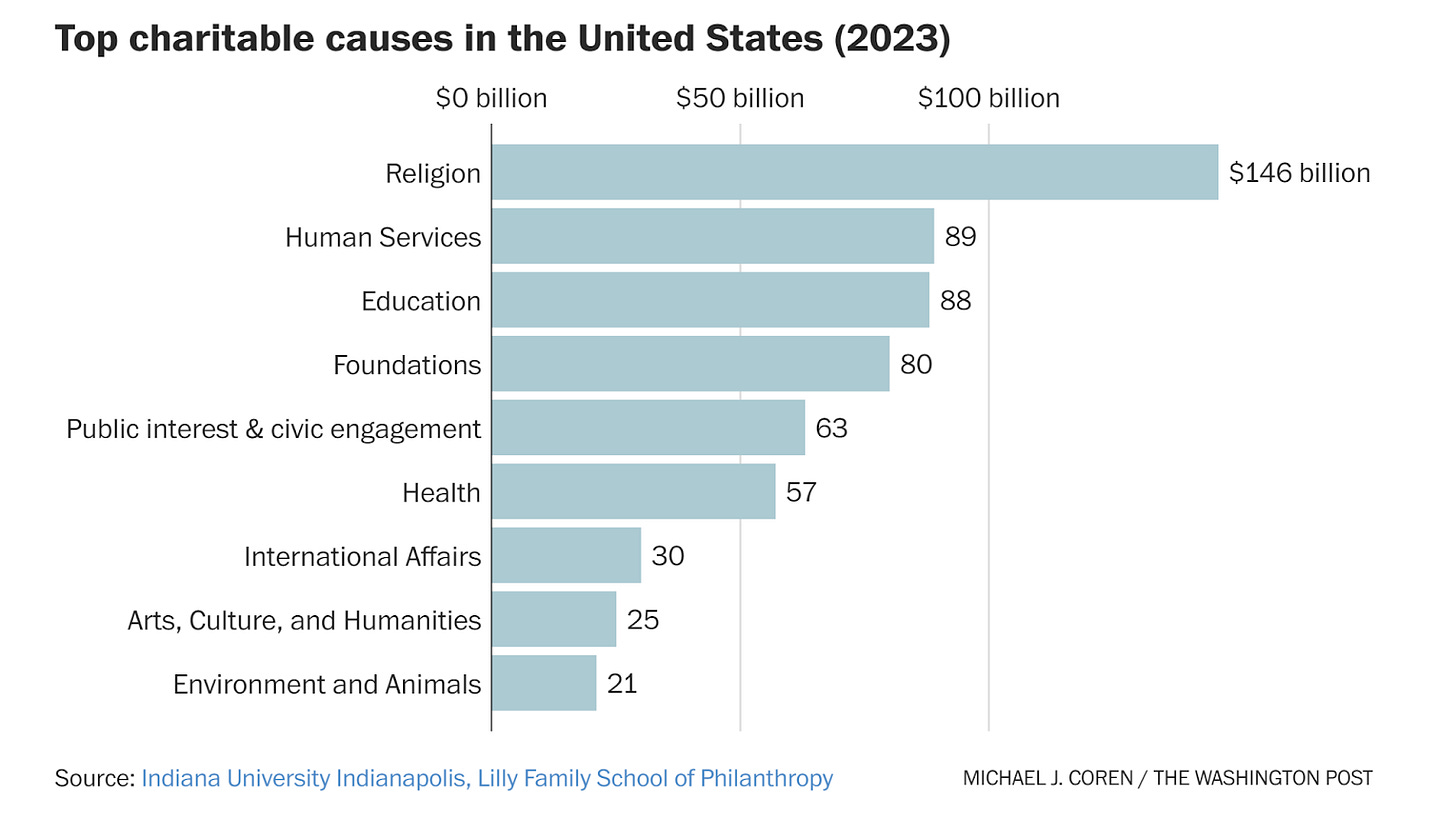

So far, the documented loss of nature and nature connection have not broadly roused Americans to action — or at least, to putting their money toward change. Environmental and animal causes rank last out of nine giving categories. Americans contribute seven times as much to religious causes as to environmental ones.

How: Planetary health is public health

I can be Pollyana-ish about the benefits of managing our home landscapes for biodiversity. And I believe doing so encourages many others to follow suit. That’s why I write this newsletter. However, I can’t imagine our individual actions will be enough to reverse the broad national — and global — trends above. You may want to join me in also taking the following actions:

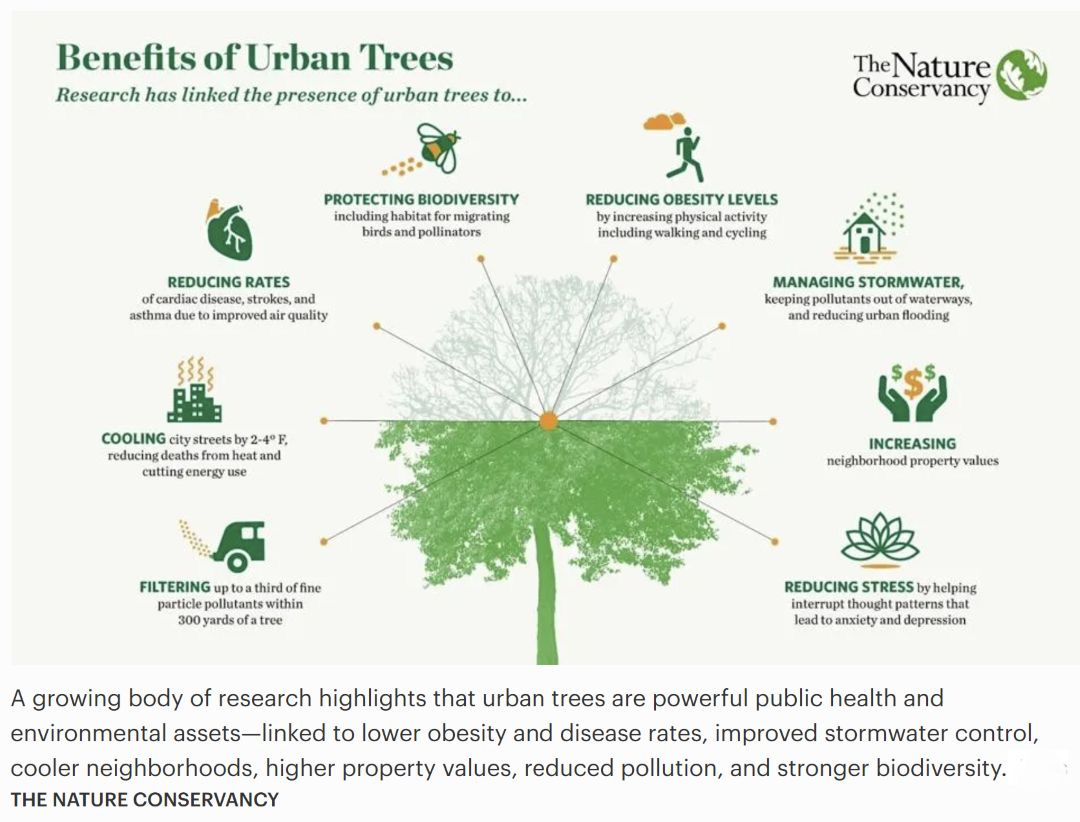

Supporting — i.e., donating to or voting for — “nature based solutions” to community problems, from infrastructure to public health to global warming. That might look like protecting a watershed, as New York City did in the 1990s, by investing $1.5 billion over 10 years in preserving its forested watershed and restoring critical habitats to protect its water at the source, rather than investing $8 to 10 billion in a new treatment plant. Or it might mean planting street trees to reduce cardiovascular risk in urban areas, as Green Heart Project, The Nature Conservancy, and NIH did in Louisville, Kentucky.

After planting more than 8,000 trees and shrubs in low-income neighborhoods with high pollution exposure, they found residents’ high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) levels — a key inflammation marker — were lower by 13-20%. These reduced levels correspond to a nearly 10-15% reduction in the risk of heart attacks, strokes, or cancer. — Forbes (read for more examples)

Donating to fund research by organizations like the Xerces Society (insects) or Cornell Lab of Ornithology or conservation of wild areas by local land trusts. (Find a local land trust at the Land Trust Alliance.)

Volunteering for grass roots organizations like Wild Ones or Pollinator Pathway, which are mobilizing communities to plant native and to change local policies to prohibit the use of pesticides and other chemicals. (You’ll benefit, too: Recent happiness research shows almost anything is better with friends. I was thrilled to meet so many like-minded neighbors when 30 people showed up for a September meeting to launch a Pollinator Pathway chapter in my Rhode Island town.)

Or simply joining the mailing list and responding to calls for action from advocacy organizations like the Sierra Club. The Florida Springs Council, for example, effectively mobilizes citizens to counteract corporate influence on state legislators. Calling the governor or sending an email to your legislator — alongside thousands of other concerned citizens — makes a difference.

Sharing information with your neighbors and HOA about the benefits of your local native plants, including lower water bills, fewer pesticides, and vibrant wildlife. If you’re in an HOA — as 70% of new homes are — consider serving on your HOA board to be an insider voice for biodiversity (see Homegrown National Park’s HOA Action Plan).

And keep on gardening on! First, it’ll keep you healthy, mentally and physically, which will help protect you from the barrage of discouraging news. Not sure how? Read Why Gardening Is So Good for You in the New York Times (gift link).

And individual conservation efforts DO make a difference. Just leaving the leaves protects thousands of insects — in each square yard.

“We actually have a lot more things emerging than I think many homeowners think we do,” [state entomologist for the Maryland Natural Heritage Program] Dr. Ferlauto said. “In a square meter of yard where you leave your leaves, there’s on average almost 2,000 insects that will emerge over the course of the spring.” — The New York Times

And planting butterfly host plants can turn around declines in individual butterfly species, as demonstrated most recently by the comeback of the Karner blue butterfly in Michigan. I’m trying to plant as many hosts as possible for this bellwether insect in my new Gainesville garden and you can, too. Use the National Wildlife Federation plant finder to identify local keystone species or this list from Prairie Nursery to find hosts of especially showy butterflies.

Finally, live near a golf course? See 4 surprising things that may reduce your risk of Parkinson’s (Washington Post gift link).

Wow!

In Veranda’s new book, Los Angeles landscape designer Scott Shrader says,

It’s my job to get people out into the garden and keep them there. … I am always looking for a new arrangement to engage people and give them something to do, even if it’s simply spending time together. — Veranda Enchanting Gardens

The following before-and-after images illustrate different ways designers draw people out into their yards to enjoy healthful human-nature connection. (If you’re ready to transform your own yard, register for my daughter Zoe and my free virtual workshop, Turn that Patch into a Plan, on December 9 at 6 pm E.T., presented by Wild Ones.)

Opening up the view in San Francisco

Believe it or not, this total transformation of the back of a San Francisco Victorian is DIY — though by an architect, Kevin Short of Tiny Monster Design, and his designer wife Katie Heller. It’s a dramatic illustration of the impact of improving the view.

Lawn to Londerful (Anyone get the Slow Horses reference?)

This is a good example of how adding plants expands, rather than decreases, the sense of space in a narrow urban yard. Open, multi-stemmed trees break the length into rooms, while vines and other greenery along the fences “blur the edges.” The lounging and dining areas and a new path to the shed-office create destinations, so the owners spend time — and entertain others — in the once bare yard. This five-week transformation cost roughly $36,000, including $12,000 for paving and $11,000 for plants.

Sharp design enhances nature in New Jersey

This “before” has a homey, naturalistic feel, but the stepping stones aren’t functional. In the “after,” the steps, which complement the modern house stylistically, draw you through the more densely planted landscape — and down to a lake below. Landscape designer Ronni Hock says,

The husband is a very busy surgeon and wanted to be able to come home, walk around to different areas outside and have places for the family to sit and enjoy the setting. — Houzz

Don’t we all?

From bare to beautiful New York City balcony

Dirt Queen NYC made this balcony welcoming to both humans and pollinators. Notice how the small trees along the left create a sense of security, while the TV — a client request — makes the seating area a destination. (See additional images at Gardenista.) Read my article about how to make small awesome.

Made in the shade in LA

Yes, the pool ($$$) makes a big difference in this transformation by Lauren Caris Cohan and her partner in life and business, Matt Jacoby. But I’d argue the furniture and additional planting — lots and lots of lush plants in what was already a wooded hillside — MAKE this backyard. Don’t you want to hang out there?

Wildr Update

In the latest episode of Walk on the Wild Side from the Less Lawn More Life team, Filippine Hoogland talks about another way we can contribute to arresting the decline of nature (and health): by becoming citizen scientists. Simply identify plants, insects, and other animals with the iNaturalist. (Who knows, if you’re looking for love, you may even find it there; read about how this couple met over their shared passion for plant parasites.)

As a New Yorker, I can attest that street trees really do make all the difference!

Thank you so much for including actionable steps that people can take to help! Just curious from your experience - do you find that people seem to care more about the environment when it's benefit is somehow related back to themselves (like being around trees and inhaling phytoncides boosts our immune system)? I'm always looking for more ways to talk about this to bring more people over to the environment side :)